The Centipede Game, a fascinating concept in game theory, presents a compelling scenario where cooperation and self-interest clash. It’s a repeated game where two players take turns adding to a growing pot of money. At each stage, a player can either “cooperate” and add to the pot, or “defect” and take the pot for themselves. The seemingly rational choice to defect leads to unexpected and often less profitable outcomes, highlighting the complexities of strategic decision-making and the influence of trust.

This exploration delves into the mechanics, theory, and real-world applications of this intriguing game.

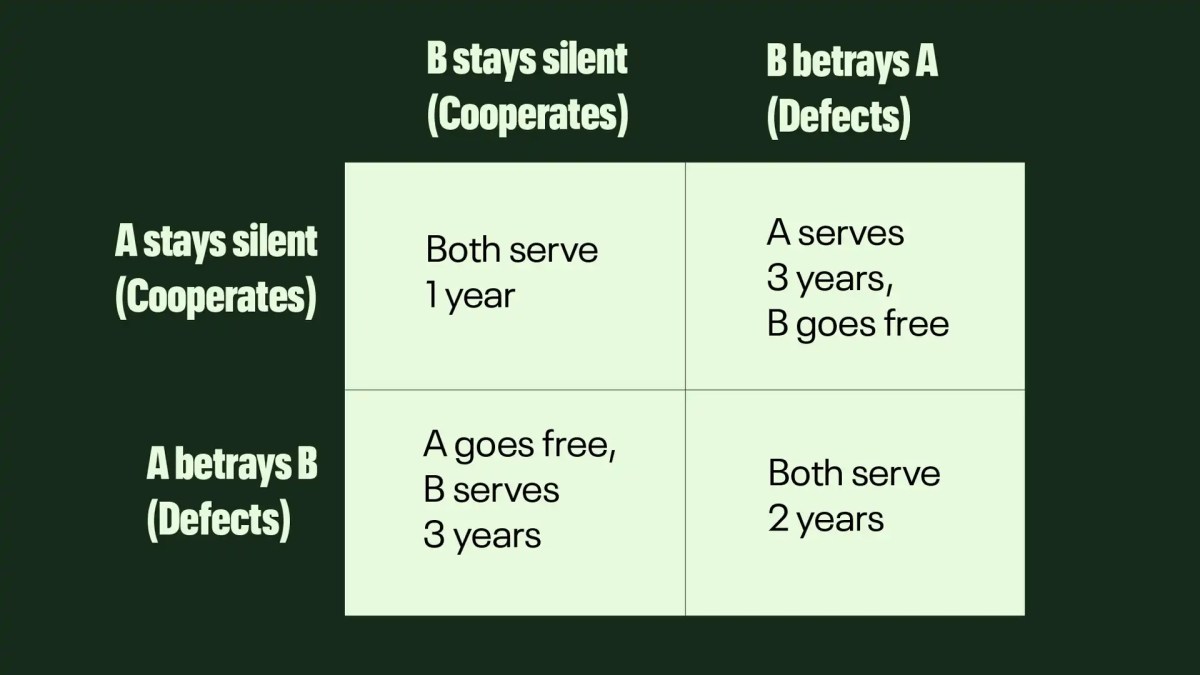

We’ll examine the core mechanics, detailing the decision-making process at each turn and outlining the payoff structures. We’ll explore the concept of backward induction and the Nash equilibrium, comparing the Centipede Game to other game theory models like the Prisoner’s Dilemma. We’ll also investigate how rational and irrational behavior influences outcomes, using both hypothetical scenarios and real-world examples such as economic interactions and political negotiations.

Centipede Game: A Deep Dive

The Centipede Game is a fascinating game theory experiment that reveals much about human behavior, rationality, and the complexities of strategic decision-making. It presents a seemingly simple scenario with surprisingly intricate outcomes, highlighting the tension between self-interest and cooperation.

Game Mechanics and Rules

The Centipede Game is a sequential game where two players repeatedly decide whether to cooperate or defect. Each round, a pot of money grows larger. If a player defects, they take a larger share of the current pot, leaving the other player with a smaller amount. If both players cooperate, the pot continues to grow until a predetermined number of rounds.

The payoff structure is crucial; it determines how much each player receives under different scenarios. A typical structure shows escalating payoffs for continued cooperation, with defection leading to immediate but potentially smaller gains for the defector, and lesser gains for the other player.

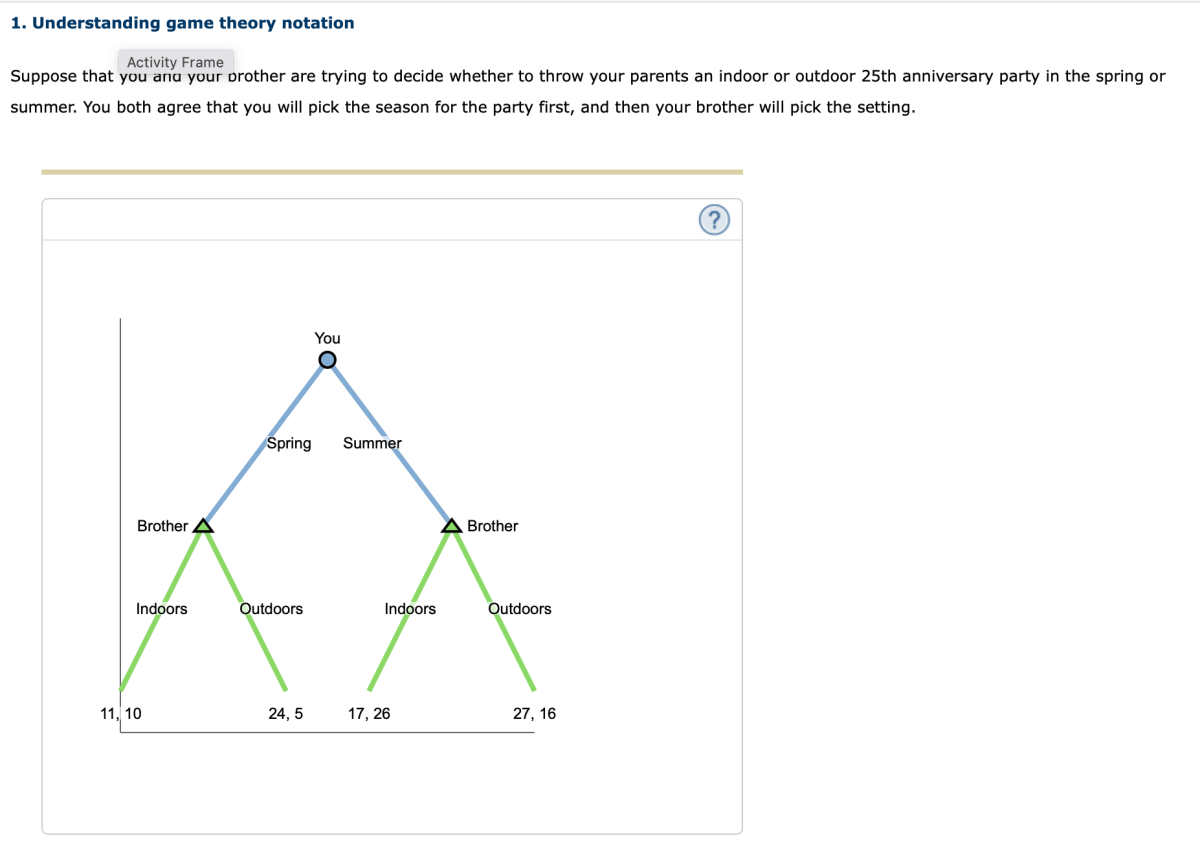

The decision-making process unfolds step-by-step. Player 1 starts, choosing to either “cooperate” (C) or “defect” (D). If Player 1 cooperates, Player 2 gets a turn to choose C or D. This continues until a player defects or the game reaches its final round. A player’s choice at each stage is influenced by their anticipation of the other player’s response and the overall payoff structure.

Here’s a step-by-step guide illustrating a 3-round Centipede Game:

- Round 1: Player 1 chooses C or D.

- Round 2 (if Player 1 chose C): Player 2 chooses C or D.

- Round 3 (if both chose C in Rounds 1 & 2): Player 1 chooses C or D.

Payoff structures vary, but a common example is: If Player 1 defects in Round 1, they get 10, Player 2 gets 0. If Player 1 cooperates and Player 2 defects in Round 2, Player 2 gets 20, Player 1 gets 5. If both cooperate until Round 3, Player 1 gets 30, Player 2 gets 25 if Player 1 chooses C, and Player 1 gets 40, Player 2 gets 35 if Player 1 chooses D in Round 3.

| Round | Player 1 Choice | Player 2 Choice | Payoffs (Player 1, Player 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D | – | (10, 0) |

| 1 | C | D | (5, 20) |

| 1 | C | C | (40, 35) |

Game Theory Concepts Applied

The Centipede Game elegantly demonstrates several key game theory concepts. Backward induction, a process of reasoning backward from the end of the game to determine optimal strategies, predicts that rational players will defect at the first opportunity. This is because, at the final stage, defection is always better for the player making the choice. Knowing this, the previous player will also defect, and so on, leading to defection in the very first round.

However, this rational prediction often fails to match real-world behavior.

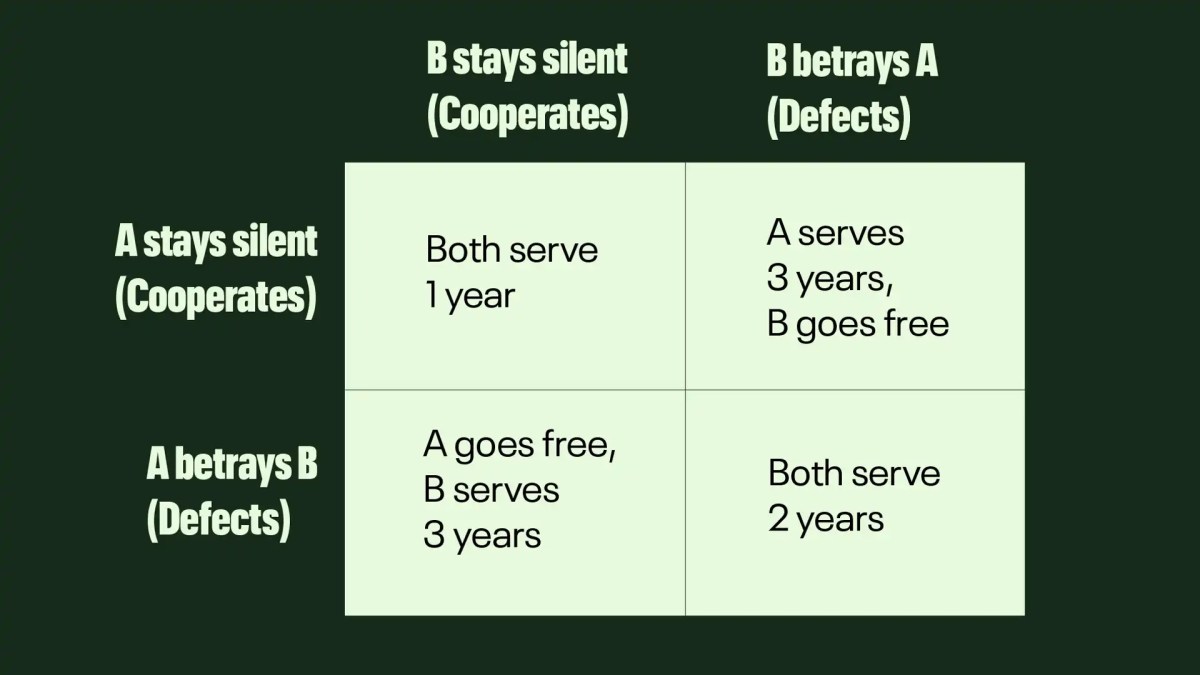

The Nash equilibrium, a solution concept where no player can improve their outcome by unilaterally changing their strategy, given the other players’ strategies, is (D, D) in the Centipede Game. This means both players defecting in the first round is a Nash equilibrium, even though it may not be the most efficient outcome. The Prisoner’s Dilemma shares similarities with the Centipede Game; both showcase the conflict between individual rationality and collective well-being.

However, the Centipede Game extends this by adding multiple stages of decision-making, making the strategic implications more complex.

Strategic implications of different choices include the risk of the other player defecting, the potential for increased payoffs through cooperation, and the possibility of mutual gains or losses depending on the chosen strategy. The longer the game, the more complex the decision-making process becomes as players weigh the immediate benefits of defection against the potential long-term gains from cooperation.

Rationality and Irrationality in Play, Centipede game

Rational players, according to backward induction, will always defect at the first opportunity. However, experimental evidence consistently shows that many players cooperate for several rounds before eventually defecting. This irrationality, from a purely game-theoretic perspective, often leads to better outcomes than predicted. Irrational behavior, in this context, might involve trust, risk aversion, or a desire for fairness.

| Strategy | Player 1 Choice | Player 2 Choice | Payoffs (Player 1, Player 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rational (Backward Induction) | D | – | (10, 0) |

| Irrational (Cooperation) | C | C | (40, 35) |

| Irrational (Cooperation then Defection) | C | D | (5, 20) |

In a hypothetical scenario, if Player 1, unexpectedly, cooperates in a 3-round game where both players had previously defected in the first round, and Player 2 also cooperates, they would both achieve a significantly better payoff than if they had both defected. However, this cooperation is risky, as it relies on trust and the expectation of continued cooperation from the other player.

Remember the classic Centipede game? The frantic dodging, the ever-increasing speed… it was intense! Now imagine that same kind of pressure, but instead of bugs, you’re dodging social awkwardness in a completely different kind of game, like the one found at dress coat video game. Then, think about applying that same strategic thinking back to your Centipede strategy – maybe you’ll find a new high score!

Real-World Applications and Analogies

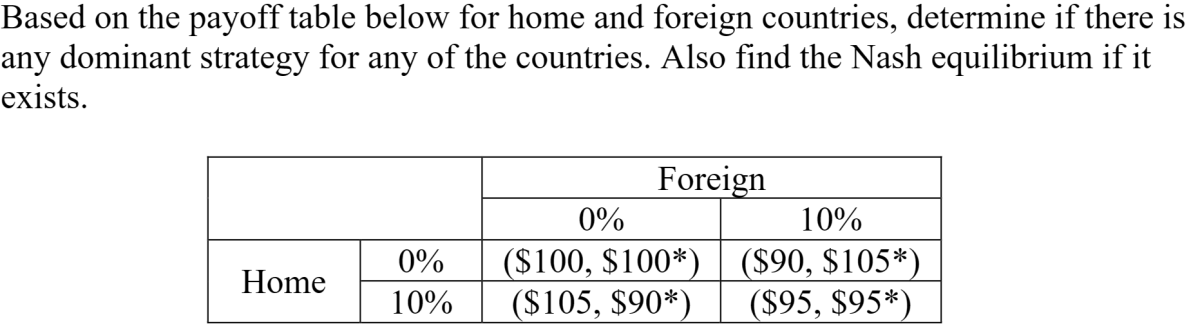

The Centipede Game’s dynamics can be observed in various real-world situations. Arms races, where countries repeatedly escalate their military buildup, mirror the game’s structure. Similarly, negotiations, such as international trade agreements or labor disputes, often involve a series of concessions and potential defections. The game can also model certain aspects of economic interactions, where firms decide whether to cooperate or compete, or political negotiations, where parties decide whether to compromise or pursue their own interests aggressively.

A case study might involve two companies negotiating a joint venture. Each round represents a stage of negotiation, with each company deciding whether to offer concessions (cooperate) or push for a more advantageous deal (defect). The final outcome depends on the companies’ risk aversion, trust, and their assessment of the potential benefits and costs of cooperation versus defection.

A simple analogy would be two people sharing a growing pile of cookies; each person can take a cookie at any time, but if they both wait, the pile grows bigger.

Variations and Extensions of the Game

The Centipede Game can be modified in several ways. Altering the payoff structure can significantly affect the outcome. For example, increasing the payoffs for cooperation can incentivize players to cooperate longer. Adding more rounds increases the complexity and the potential for unexpected outcomes. Increasing the number of players introduces additional strategic considerations, as players must anticipate the actions of multiple opponents.

A hypothetical variation might involve introducing a third player, where each player can choose to cooperate or defect sequentially. This creates a more complex game with additional strategic interactions. The number of possible outcomes expands significantly compared to a two-player game.

| Variation | Key Difference | Impact on Game Dynamics | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric Payoffs | Unequal payoffs for cooperation and defection | Shifts the balance of power between players | One player gains more from defection than the other |

| More Rounds | Increased number of decision points | Increases complexity and potential for cooperation | 10 rounds instead of 3 |

| More Players | Multiple players making sequential decisions | Introduces coalition formation and complex alliances | Three players instead of two |

Illustrative Examples and Scenarios

In a scenario where two players reach the final stage of a 5-round game, and both have cooperated thus far, the decision becomes highly complex. Player 1 faces a choice: defect and take a significantly larger share of the pot, potentially risking Player 2’s future cooperation, or cooperate, hoping Player 2 will reciprocate and both players receive a substantial payoff.

Player 2’s decision will depend on their observation of Player 1’s behavior and their assessment of Player 1’s trustworthiness.

In a game where Player 1 chooses to cooperate, and Player 2 defects, Player 2 receives a larger immediate payoff, but Player 1 receives a smaller payoff than if they had both cooperated. This illustrates the potential risk of cooperation and the temptation of defection, even if it leads to a less efficient outcome overall.

The Centipede Game shows how rational choices can lead to suboptimal outcomes. Think about it: you could cooperate and potentially gain a lot, or defect and grab a smaller but guaranteed win. It’s all about trust, similar to the precision you need when flying a drone, like this awesome dji flip drone only which requires a steady hand and careful planning.

The Centipede Game’s unpredictable nature mirrors the challenges of aerial maneuvers, highlighting the complexity of strategic decision-making.

| Round | Player 1 Choice | Player 2 Choice | Payoffs (Player 1, Player 2) (Hypothetical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | C | – |

| 2 | C | C | – |

| 3 | C | C | – |

| 4 | C | D | (15, 60) |

| 5 | – | – | – |

The game’s outcome is heavily influenced by risk aversion and trust. Risk-averse players might defect earlier to secure a smaller but guaranteed payoff, while trusting players might cooperate longer, hoping for a larger payoff. The level of trust between the players is a crucial factor determining the final outcome.

Final Summary

The Centipede Game offers a captivating lens through which to examine human behavior in strategic situations. While rational analysis suggests defecting early, the game often reveals the surprising power of cooperation and trust, even in scenarios where self-interest seemingly dominates. Understanding the Centipede Game provides valuable insights into the complexities of decision-making, the limitations of purely rational models, and the significant role of factors like risk aversion and trust in shaping outcomes.

Its applications extend far beyond theoretical game theory, offering a framework for understanding interactions in diverse fields, from economics and politics to interpersonal relationships.

Questions Often Asked

What is the optimal strategy in the Centipede Game?

According to backward induction, the optimal strategy is to defect immediately. However, in practice, cooperation often occurs, demonstrating the limitations of purely rational models.

How does the number of stages affect the outcome?

Increasing the number of stages can increase the likelihood of cooperation, as the potential payoff at later stages becomes more significant.

The Centipede Game is a classic example of game theory showing how rational choices can lead to suboptimal outcomes. Think of it like this: you’re presented with a choice, and so is your opponent, and the stakes increase with each round. It’s a bit like the strategic planning needed in a game like the aloft game , where coordinated drone movements are crucial for success.

However, unlike the relatively predictable nature of drone swarms, the Centipede Game’s unpredictable human element makes it far more complex.

Can the Centipede Game be applied to real-world negotiations?

Yes, it can model situations where two parties must decide whether to cooperate or compete, such as arms races or international agreements.

What are some common mistakes players make in the Centipede Game?

Overestimating the rationality of the other player and underestimating the importance of trust are common mistakes.